“ESG” in the Financial Sectors

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Climate Change “Adaptation”

To date, the international community has dealt with climate change principally by promoting the mitigation of greenhouse gases (GHG). The rationale for mitigation efforts is that the severity of climate change can be alleviated by stabilizing or reducing the concentration of greenhouse gases. Mitigation activities are clearly necessary to the long-term well-being and stability of the global environment. However, the level of attention given to mitigation-oriented science, technology, methodology, and policy — by the popular press, practitioners, regulators, and Congress—has served to obscure the pressing need to address adaptation to climate change.

Climate Change is Inevitable

According to Ira Feldman, the reality is that, even if the most optimistic mitigation plans were adopted and all greenhouse gases were stabilized immediately, residual concentrations within the atmosphere will continue to create adverse consequences well into the future. A stable climate can no longer be assumed. Mitigation of greenhouse gases can minimize the long-term impact to the climate, but cannot halt or avoid all impacts. Human-induced climate change is going to proceed and perhaps worsen with time. Adapting to the adverse impacts of climate change is a reality.

It is clearly necessary to continue to pursue GHG mitigation strategies as aggressively as possible. However, at the same time, we should begin to implement adaptation strategies as a complement to mitigation efforts. The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report-Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerabilitysuggests “a portfolio of adaptation and mitigation can diminish the risks associated with climate change.” The report recommends that a portfolio or mix of strategies should include “mitigation, adaptation, technological development (to enhance both adaptation and mitigation) and research (on climate science, impacts, adaptation, and mitigation). Such portfolios could combine policies with incentive-based approaches and actions at all levels from the individual citizen through to national governments and international organizations.

Adaptation – Reactive or Anticipatory (Proactive)

Adaptation can be reactive or proactive. Given the exponential rate of climate change and the impacts that are currently being observed, reactive adaptation is understandable and necessary. However, reactive approaches can be costly. This is why long-term strategies for adaptation need to be considered now and integrated into current climate action plans or addressed in concert with these action plans.

Adaptation actions and strategies present a complementary approach to mitigation. While mitigation can be viewed as reducing the likelihood of adverse conditions, adaptation can be viewed as reducing the severity of many impacts if adverse conditions prevail. However, adaptation is a risk-management strategy that is not free of cost nor foolproof, and the worthiness of any specific actions must therefore carefully weigh the expected value of the avoided damages against the real costs of implementing the adaptation strategy. (Pew Center Report on Coping with Global Climate Change – the Role of Adaptation in the United States.)

Adaptation Planning at the State and Local Levels in the U.S. Some states are already considering climate change adaptation issues and either are creating separate adaptation commissions or committees to complement mitigation efforts or are integrating adaptation into the state’s action plan. As of 2007, 35 states have created or are in the process of creating climate action plans, with 14 new plans due to emerge in 2008. A number of these states have added adaptation considerations into the scope of their climate action plans.

A few examples of adaptation tools and/or strategies already being considered are:

- Translocating crops

- Switching crops and cultivers

- Adjusting planting seasons

- Changing land use allocations

- Changing water storage, supply and distribution methods

- Improving water conservation

- Water transfer strategies

- Changing coastal development

- Redefining flood plains

Collaborative Governance & Institutions

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Disclosure and Reporting

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Ecosystem Services & Markets (click here to expand or close topic)

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Environmental Performance & Sustainability Metrics

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

ISO 14000 Series

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

ISO 26000 & CSR

“Sustainable business for organizations means not only providing products and services that satisfy the customer, and doing so without jeopardizing the environment, but also operating in a socially responsible manner. Pressure to do so comes from customers, consumers, governments, associations and the public at large.”

from “ISO and Social Responsibility”

What is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)?

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a model in which an organization acknowledges its accountability to its stakeholders and environment. In this context, the term “stakeholder” encompasses everyone the organization affects, including the traditional investor and customer corporate stakeholders, as well as employees, communities, suppliers, regulators, and society as a whole. Without external enforcement, socially responsible corporations seek to reduce the negative impact of their activities. Core issues that are usually addressed in CSR include:

- Environment

- Human rights

- Labor Practices

- Fair Operating Practices

- Organizational Governance

- Consumer Issues

- Community and Society

Proponents of CSR note that the long-term strategizing that goes into implementing CSR practices can enhance an organization’s overall efficacy. With the public increasingly expecting socially responsible practices, an organization can boost its image by engaging in CSR planning. However, critics of CSR suggest that some businesses may be adopting superficial changes to capitalize on the public relations boost of appearing socially responsible. Although corporate social practices may encounter government or other external oversight during instances of extremely negative activities (e.g., human rights violations or environmental crises such as an oil-spill), there is not yet a clearly established set of guidelines for implementing effective CSR.

ISO 26000 will add value to existing initiatives for Social Responsibility by providing harmonized, globally relevant guidance based on international consensus among expert representatives of the main stakeholder groups and so encourage the implementation of best practice in Social Responsibility worldwide.

“ISO and Social Responsibility”

Establishing Global Standards: ISO 26000

In 2005, ISO established a Working Group to develop ISO 26000, a new set of standards and guidance for implementing socially responsible practices. The core issues being addressed in these standards reflect the same core issues that comprise CSR, with the scope widened to also address social responsibility in non-corporate organizations (e.g., governments, NGOs, etc). ISO 26000 will comply with existing SR standards (e.g., ILO, SA8000, Declaration of Human Rights), while accounting for the range of definitions of “Social Responsibility” already being implemented by independent SR programs across the world.

The goal of ISO 26000 is to enhance and encourage SR efforts in organizations across the world by establishing common means of evaluation, defining SR concepts, and sharing examples of best practices. The practices set forth in ISO 26000 will be voluntary standards and guidance for achieving socially responsible practices, rather than certification requirements.

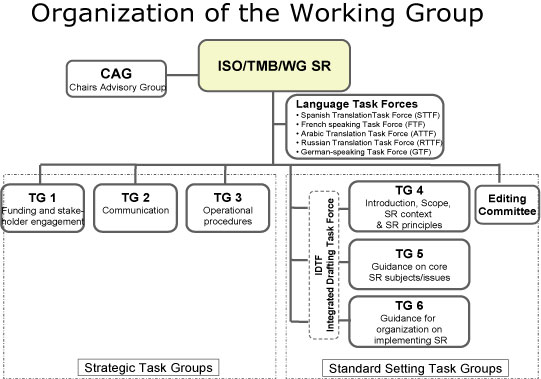

ISO 26000 is being developed through a multi-stakeholder process—ISO’s first utilization of this approach. The Working Group includes participants from across the world, representing developed and developing nations, and the six stakeholder categories of industry; government; consumer; labor; NGOs; and service, support, and research. To facilitate effective participation by the stakeholders, six Task Groups have been created within the Working Group. Three Task Groups focus on administrative strategy tasks, while the other three Task Groups focus on writing the standards (see figure below).

ISO 26000 is still under development, with a final publication date slated for mid-2010. In keeping with that timeline, the fourth Working Draft of ISO 26000 is scheduled to be released in June 2008. At this point in the process some key issues, such as establishing a standardized definition of “sustainability,” are not yet resolved.

Further Resources

- “Social Responsibility”

- “Executive summary on ISO and social responsibility”

- “ISO 26000 (CSR Guidance)”

- “ISO and Social Responsibility” (PDF)

- “SAI Home.” Social Accountability International.

- “Corporate Sustainability.” Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes.

- “ILO Home.” International Labour Organization.

- “What is CSR?” csrnetwork.

Mandatory Regulation & Voluntary Standards (click here to expand or close topic)

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Multi-stakeholder Dialogue & Partnerships

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

National Sustainability Policy – US

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Regulatory Innovation & “Next Generation”

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Soft Law, generally

“My point is that this distinction between enforceable “hard” law and unenforceable, but normatively significant, “soft” law is not limited to international law questions and thus helps us understand how powerful concepts like sustainable development grow in relevance to domestic law practitioners.”

J. B. Ruhl, “The Seven Degrees of Relevance: Why Should Real-World Environmental Attorneys Care Now About Sustainable Development Policy?”

Soft law is a term used to describe a quasi-legal function. Soft law can be found in documents, statements, guidelines, codes of conduct, principles, action plans, declarations, resolutions, and codes of ethics traditionally found in the international arena, although it is surfacing in domestic instances as well. The terminology evolved because of the particular function it served. Essentially providing a framework of guidelines and expectations, soft law lacks the “teeth” that real law, or “hard law,” can have. Soft law has the potential of becoming “hard law” and morphing into a treaty, contract, or rule of law.

Societal norms and expectations play a large role in law. In common law systems, many laws are self-perpetuating. A law is placed into existence and is then reinforced by interpretations of existing factual circumstances, which also reinforce the norms. If an individual varies from the norms and disobeys the law, the injured party can bring enforcement of these norms through a regulatory agency or a court of law. Soft law, on the other hand, is a set of expectations and norms with neither a formalized framework nor a threat of enforcement.

Therefore, soft law has become important in the fields of international environmental law, international economics law, and international sustainable development law, where consideration of varying approaches to balancing environmental initiatives with socioeconomic factors in divergent cultures and governments is critical to the formulation and promulgation of initiatives.

Hard Choices, Soft Law: Voluntary Standards in Global Trade, Environment and Social Governance, by John J. Kirton and Michael J. Trebilcock is a collection of essays on how soft law works in international politics. The book’s 18 essays cover a range of topics, some of which include: setting standards for sustainable forestry, corporate conduct codes and labor regulation in developing countries, trade policy and labor standards, the role of nongovernmental organizations and social movements in developing countries, and integrating environment and labor into the World Trade Organization.

Environmental law has been affected by the use of soft law, especially in the European Union. In the article, “Soft Law, Self-Regulation and Co-Regulation in European Law: Where Do They Meet?,” Linda Senden notes that the European Union has embraced a model of “do less in order to do better,” whereby deregulation, simplification, and voluntary agreements are utilized. The EU is attempting to achieve harmony by trying to be flexible and diverse and not necessarily uniform, but merely coordinating national policies. In the EU context, variations of soft law aid in the development of self-regulation and co-regulation. A communication may be written from the government instructing all parties in voluntary environmental agreements that the objectives of a particular treaty must be met. In some cases, voluntary self-regulation has ensued, as when a group of interested parties has reached voluntary agreement on some topic and informed a governmental authority, which then performs the non-binding act of sending a recommendation.

Further Resources

- Senden, Linda. “SOFT LAW, SELF-REGULATION AND CO-REGULATION IN EUROPEAN LAW: Where Do They Meet?” Electronic Journal of Comparative Law, vol. 9.1 (January 2005). http://www.ejcl.org

- Gralf-Peter Calliess & Mortiz Renner; “From Soft Law to Hard Core: The Juridification of Global Governance.” This paper is based on a presentation given at the workshop “Law after Luhmann: Critical Reflections on Niklas Luhmann’s Contribution to Legal Doctrine and Theory” in Oñati (Spain), July 5-6, 2007.

- Hillgenberg, Hartmut. “A Fresh Look at Soft Law.” EJIL (1999), Vol. 10 No. 3, 499-515

- Shelton, Dinah L. “Soft Law.” The George Washington University Law School Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper No. 322.http://ssrn.com/abstract=1003387

- John J. Kirton and Michael J. Trebilcock(editors) Hard Choices, Soft Law: Voluntary Standards in Global Trade, Environment and Social Governance

Strategic Environmental Management Tools (click here to expand or close topic)

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Sustainability Policies – Other countries

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Sustainable Business Practices/ Triple Bottom Line

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.

Sustainable Business Practices/ Triple Bottom Line

“We believe that corporations must conduct their business as responsible stewards of the environment and seek profits only in a manner that leaves the Earth healthy and safe. We believe that corporations must not compromise the ability of future generations to sustain their needs.”

from the CERES pledge

“In its broadest sense, the triple bottom line captures the spectrum of values that organizations must embrace—economic, environmental and social. In practical terms, triple bottom line accounting means expanding the traditional company reporting framework to take into account not just financial outcomes but also environmental and social performance.”

John Elkington, Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business.

Sustainability in business has come into prominence in the last two decades; as sustainable development becomes a concern for communities around the globe, the cry has gone out for sustainable policies in every aspect of life. As the public becomes better educated about environmental concerns, the expectations grow for the corporate world to answer to those concerns. The driving force behind sustainable communities is integration, and people are starting to seek that out in corporate culture as well. They want to see companies that are reaching out to their communities and their employees.

One way of looking at the goal of sustainable businesses is an idea known as the “Triple Bottom Line,” which is the idea of companies shifting their priorities and expanding their emphasis from profit to include environmental and social growth as well—combining economy with ecology. This means not only adopting more environmentally sound practices, like reducing carbon emissions and improving recycling, but also dealing with social issues, like corporate corruption and fair labor practices. The public is increasingly interested in being associates, as employees and customers, of companies whose values and priorities they share. Adapting a company’s philosophy to accommodate sustainability is not just a trend or a way to appease public opinion, but a genuinely valuable and necessary investment in the future health of a company.

There are many resources for companies that are beginning to adopt sustainable business practices. The ISO 14000 standards, a result of the UN Rio Summit in 1992, are a set of environmental measures and standards for companies to measure their progress in becoming more environmentally viable. Shortly after the publication of the World Commission on Environment and Development report written by the United Nation’s Brundtland Commission in 1987, the International Chamber of Commerce developed a “Business Charter for Sustainable Development,” which sets out 16 principles for environmental management.

There are many non-profit organizations and consulting companies (e.g., the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies, Businesses for Social Responsibility) dedicated to sustainable practices. Corporations that are well known for years of interest in sustainable business policies include Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream and Starbucks. Ben & Jerry’s, a member of CERES organization, has published a Social and Environmental Assessment report every year since 1989, which includes reviews of their sustainability-promoting activities each year. Starbucks has made a shift to buying certified organic and shade grown coffee. They have also taken stewardship of many small coffee growing communities, implementing social programs such as the building of health clinics and schools, and creating loan programs so local farmers can retain ownership of their farms.

Further Resources

- United Nations: General Assembly. “Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.” http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/42/ares42‑187.htm

- The International Chamber of Commerce. “Business Charter for Sustainable Development.” http://www.bsdglobal.com/tools/principles_icc.asp

- User Forum for the ISO 14000 Standards. http://www.14000.org/

- Ceres (investors and environmentalists for sustainable prosperity). http://www.ceres.org/NetCommunity/page.aspx?pid=705

- “Businesses and Sustainable Development: a global guide” http://www.bsdglobal.com/tools/principles_sbp.asp

- Businesses for Social Responsibility (a consulting firm for businesses to advise them and help implement more sustainable practices). http://www.bsr.org/

- International Fair Trade Organization. http://www.ifat.org/

- http://www.greenbiz.com/ (A website dedicated to articles on green business, sustainability in business, climate concerns, and other related issues; updated daily.)

Sustainable Communities

“Sustainable Development is a broad concept that recognizes the linkages between actions and their impact on economic development, the environment, and social well-being. While it is generally accepted that development should be sustainable in all three of these dimensions, practical application of the concept is complex and challenging.”

from “Sustainability Assessment for West Virginia”

Sustainable communities are communities of any size, from large metropolitan areas to college campuses and rural villages, that are dedicated to using natural resources in the most efficient and beneficial way possible. The goal is to be able to create a community that provides for all the needs of every member while maintaining a healthy balance with the environment, reducing the carbon-footprint, and cleaning up existing resources like air, water, and soil. Government regulations on factory emissions, farming education programs, and the use of “green” energy sources such as solar power are just some of the various means to sustaining healthy communities.

Sustainable development was first introduced as a global concept by “Our Common Future,” a report prepared by the United Nation’s Brundtland Commission in 1987. It presented a number of growing global issues such as population increase, urbanization and industrial development, endangered species, and ecosystem imbalances. The 1987 report was the first global request for governments at every level to begin assessing their capabilities for change towards a more sustainable community model. The central idea behind sustainable community building is to create a community in which environmental and social responsibility is integrated into every aspect of that community. This means creating more local jobs, allowing less industrialization, and encouraging people to take active roles in their own communities. Ownership and education are key. People are encouraged to develop their own solutions instead of waiting for someone to do it for them, which gets ordinary people involved in problem-solving in conjunction with their local government and non-profit organizations.

Many small communities around the globe are working towards sustainability, and are reducing their negative impact on the environment. For example: the village of Ashton Hayes in Cheshire is aiming to become the first carbon neutral village in England; the EcoVillage in Ithaca, NY employs all organic farming and has restored more than 80% of its land to green space; and the small village of Gaviotas in Columbia, South America farms using wind and solar energy and has planted extensively, reviving acres of indigenous rainforest. These communities, and many like them, employ a variety of resources made available by non-profit organizations such as the Institute for Sustainable Communities, the Global Development Research Center, and ICLEI’s Local Governments for Sustainability. These and other organizations provide tools such as community planning guides, environmental studies, education programs, technical expertise, and leadership training.

Further Resources

- United Nations: General Assembly. “Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.” http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/42/ares42-187.htm

- Information regarding Local Agenda 21, a plan formulated and signed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. http://www.gdrc.org/uem/la21/la21.html

- UN Education. “Framework for a Draft International Implementation Scheme.” http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23365&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

- Davis, Thomas. “What is Sustainable Development.” http://www.menominee.edu/sdi/whatis.htm

- A list and brief descriptions of sustainable communities in the US and around the world. http://www.ecobusinesslinks.com/sustainable_communities.htm

- Institute for Sustainable Communities. http://www.iscvt.org/

- ICLEI. Local Governments for Sustainability. http://www.iclei.org/index.php?id=global-about-iclei

- Global Development Research Center. http://www.gdrc.org/

- United Nations. “Decade of Education for Sustainable Development.” Homepage. http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=27234&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201

Transboundary Issues

Contact Ira Feldman for more information on this topic.